Bede inspires as we emerge from Covid-19

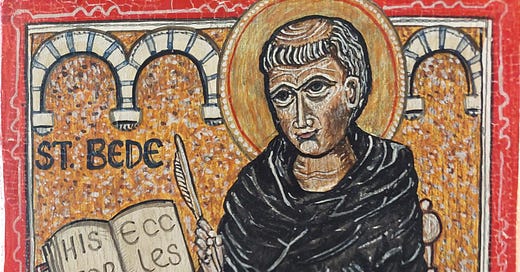

It is widely recognised that St Bede (d. 735), whose venerable body lies in the Galilee Chapel of Durham Cathedral, played a vital role in the transmission of early Christian teaching—including the thought of St Ambrose of Milan (d. 397) and St Augustine of Hippo (d. 430)—to subsequent generations of theologians, and his Ecclesiastical History of the English People continues to be regarded as a preeminent source for early medieval religious history.

Bede was also a prolific preacher, composing many homilies, uncovering the meaning of passages from scripture, which have resonated with communities of faith and scholarship down the centuries. They are a testament to intense spiritual love, first for God and then for the whole of God’s creation, not to mention a capacity for the poetic expression of Christian truth:

God’s word [is] indeed like spices—the more finely it is crushed by handling and sifting, the greater is the fragrance of its inner power that it gives forth.1

Recent scholarship has begun to piece together a picture of Bede’s spiritual personality, suggesting that behind the intellectual lay a man of passionate faith, self-aware, and capable of emotional outpourings of great range and depth.

The quotation above, comparing God’s word to spices, comes from a homily for Easter, in which a bold and timeless Bede imparted a message with acute contemporary relevance. The text as a whole was a reflection upon the culmination of Matthew’s gospel with one of Jesus’ posthumous appearances to his followers: ‘the eleven disciples went to Galilee, to the mountain to which Jesus had directed them. When they saw him, they worshipped him; but some doubted’ (Mt 28:16-17).

As the Christian community looks forward to the imminent lifting of Covid-19 restrictions, it may be appropriate to ascribe to Easter 2021 Bede’s interpretation of the name ‘Galilee’, described here as the meeting place of Jesus and his disciples: ‘Galilee means “a crossing over accomplished” or “revelation”.’ It was appropriate for Jesus, having recently passed over from death to new life, to encounter his friends at Galilee. It is also the sincere hope of many that this Easter will mark a crossing over from the darkness and misery of disease to the recovery of life together.

Bede’s homily taught that the first Easter revealed the exaltation of humanity after a time of testing, since Christ triumphed over death not only as God, but as God made flesh. In an equivalent way, perhaps this Easter will be marked by a renewal of humanity. Perhaps the stripping back of life has fostered a new awareness of our vulnerability and need for community, as well as a certain capacity for goodness, which may help to guide the future.

Bede’s homily also drew attention to the most ominous phrase in the gospel text: ‘but some doubted’.

The grandeur of his account of the renewal of human life brought about by Jesus was combined with an admission that, whether from fear or another kind of mental disturbance, some of the disciples simply could not accept the reality of his presence. This salutary insight, at the heart of Bede’s vision of the first Easter, will resonate with many people today. Even though restrictions are being lifted, the legacy of a challenging (even, devastating) experience will be long-lasting and many different anxieties will prevent some from grasping opportunities for renewal as quickly as others. We should be ready to support those who may be afraid.

The wisdom of Bede’s vision for Easter, to which we may continue to look for inspiration and encouragement, resided in a combination of a great hope for renewal with a gentle forbearance towards human frailty. Unpacking the meaning of the term ‘Galilee’ for his medieval audience, Bede also seems to speak into and for our own times, formed as they are by both optimism and trauma. Easter 2021 may indeed mark a ‘crossing over’ from darkness to light, a genuine resurrection of the human spirit and of society, but it will also take place gradually, as with all Easters, beginning with the kindling and sharing of the little light of the Paschal Candle.

The latter has been beautifully expressed by the medieval scholar, Sr Benedicta Ward:

This is the time of a new beginning, a new creation . . . There is in this moment of darkness a sense of alienation, of exile, of not being at home . . . From the rock of the tomb a new light is struck from flint and shines into darkness. A candle is lit and from it small candles take their light, so that behind each small candle-flame there is the face of a human person newly made in Christ whose identity in the darkness is that of this new light.2

Bede, Homilies on the Gospels, II: Lent to the Dedication of the Church, trans. by Lawrence T. Martin and David Hurst (Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1991), pp. 69-77 (II. 8).

Benedicta Ward, SLG, In Company with Christ: Through Lent, Palm Sunday, Good Friday and Easter to Pentecost (Oxford: Fairacres Publications, 2016), p. 42.

An earlier version of this post was prepared for the blog at Durham Cathedral.